He Gave Us Smokey the Bear

American Legion Magazine, January, 1977

Albert staehle was my husband. His name may not mean much to the average person, but any schoolchild knows his "Smokey the Bear."

For over 50 years Al Staehle, Smokey's creator, painted illustra¬ tions that have become part of Americana and have found a place in the hearts of animal lovers every¬ where. This is my tribute

to him.

Al came from a long line of artists. His father, an American illustrator who painted for Currier and Ives was' studying art in Munich, Germany when he met and married the daughter of the Court Painter to the Royal House of Bavaria. Albert was born in Germany to American citizenship in 1899.

"I started to draw as soon as I could hold a pencil," he said.

Success came early. In 1918, he entered a poster competition. His picture of a cow feeding her calf a bottle of milk and saying, "Nothing's Too Good For My Baby" won the first prize by public vote (not the advertising hierarchy). The Borden Company was working on an idea so similar that they bought Al's picture to protect patent rights. The idea evolved into Elsie the Cow.

After that he had all the work he could handle; the swan for the soap of the same name, rabbits, birds, tgers, monkeys, a gorilla, bears and numerous cats, kittens, dogs and puppies. All peered out from national advertisements on posters, billboards and magazines all over the United States. A number appeared on American Legion Magazine covers.

The love affair began in a pet shop window. Saturday Evening Post editors were looking for a cover sub¬ ject to boost newsstand sales and decided a puppy would be a good subject. Al was asked to come up with some sketches. A passing glance into a Greenwich Village pet shop window met the pleading eyes of a six week old cocker spaniel.

Butch and Al Staehle did their job well. Whenever a "Butch" cover ap¬ peared, it was number one in news¬ stand sales. Fan mail came from everywhere. Most of it was ad¬ dressed to 1he mischievous pup. Sometimes letters were sent to the artist asking him not lo be too hard on the dog for the many pranks he played. Once, when a cover depicted Butch running through the house unraveling a roll of tissue, a case of toilet tissue arrived from a fan with a note to please let Butch enjoy him¬ self. Another cover, during World War II, showed the dog chewing a book of ration stamps. This brought a number of coupons in the mail.

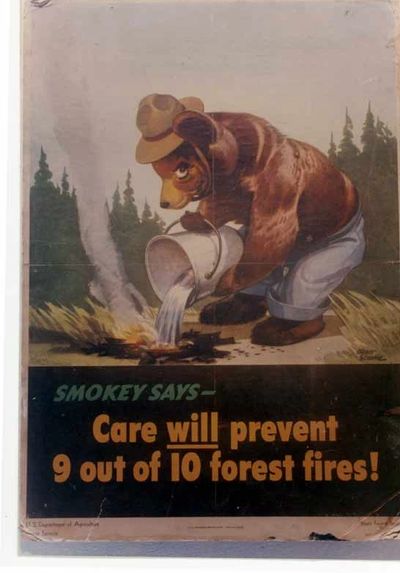

The U.S. Department of Interior wanted a mascot for its forest fire prevention campaign and Al was asked to collaborate. The Rangers suggested a woodchuck or a raccoon.

"The raccoon looks too much like a burglar," Al protested. So they settled on a bear.

"I felt a bear could be portrayed as the father of the forest." Al explained.

The bear was fitted with a ranger's hat and badge, blue jeans and a pail of water to put out fires. He was named after Smokey Joe Ryan, a fa¬ mous New York Fire Chief. Smokey was part of the war effort and Al received only "expenses" for his post¬ ers. (The original brown bear who symbolized "Smokey" recently died.) The monies which continue to come from various Smokey enterprises go to forest education.

Al never forgot it was the popular vote that launched his career and he always wanted to paint for every¬ one. When he died in 1974, we planned a memorial show of his work, but instead of using a fine art gallery or "select" museum, we chose Miami Dade Community College and Dade County Museum of Science and Planetarium. Both are frequented daily by busloads of visitors, tourists and lots of children.

Al would have liked it.

-Marjory Houston Staehle

The first Smokey the Bear Poster

He Gave Us Smokey the Bear

'Butch' the Cover Dog

'Smokey the Bear' , Albert Staehle and 'Butch' the dog

'Smokey the Bear' , Albert Staehle and 'Butch' the dog

'Butch', Al's real-life model dog appeared on many magazine covers; The Saturday Evening Post, American Weekly

'Smokey the Bear' , Albert Staehle and 'Butch' the dog

'Smokey the Bear' , Albert Staehle and 'Butch' the dog

'Smokey the Bear' , Albert Staehle and 'Butch' the dog

Al Staehle, center, Gave us Smokey the Bear (left). Butch (right and lots of memories.

Copyright © 2024 Albert Staehle - All Rights Reserved.

seleneh@bellsouth.net